INTRODUCTION

Founded in 1993, the AM Qattan Foundation is a registered charity in the UK which operates out of premises in London, Ramallah and Gaza. It works towards the development of culture and education, with a particular focus on children, teachers and young artists. For more information on the AMQF including its vision and values, click here.

Having outgrown its existing accommodation in Ramallah, the AMQF is planning to construct new premises in the Tireh area of Ramallah. It is running an international architectural competition for the design of what will be a major new cultural center and office building.

The competition is an opportunity to champion excellence in design, reflecting the quality of the AMQF’s work in the culture and education fields for over 15 years. As well as responding to the AMQF’s functional needs, the new building is expected to set a standard for the architecture of subsequent public buildings in Palestine.

The AMQF hopes that the competition and execution process will raise awareness about the role of the built fabric design in improving the quality of urban life in social, cultural and economic terms.

Coming from abroad, the Qattan Foundation is perceived as a lighthouse bringing enlightenment to the Palestinian people. This role as a flagship of Palestinian culture is in need of a recognizable image worthy to represent its social leadership with a physical landmark. We imagine this landmark as a light up the mountain, seen from everywhere and, although modern and contemporary in its form, it is built from the very earth and stone of Palestine. The future building will target an international audience with a contemporary language, but what it will deliver is the local vernacular and very particular qualities.

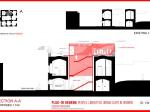

As a building bound to the ground, it is designed to be in harmony with its physical setting, while taking advantage of the site’s features. The main body is conceived as a stone plinth carved in terraces out of the natural soil, enhancing the interior-exterior relation through the use of lattices and natural stone permeable screenings. This innovative and contemporary use of the local stone will be used to clad entirely a tall transparent volume seating on top of the plinth. This volume will therefore perform like a lighthouse, a glittering landmark on top of the hill.

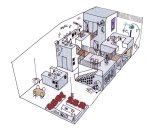

The distribution of uses is based on a suitable relation between public and private uses. Most public spaces and common facilities (art gallery, residence and parking lot) are located within the plinth, whereas the rest (library, multipurpose space, storage/workshop space and book cafe) are located where the tower meets the plinth. The tower will house those uses in need of privacy and certain security, like the General Management, QCERD and CAP, all conceived as open plan working spaces with enclosed private office spaces. In order to supply the building with no disruption to its normal functioning, an independent loading bay will be arranged at the multipurpose hall level from a private lane perpendicular to the main street.

Human scale spaces and elements are introduced in order to make the building softer and comfortable. Vegetation will grow in the courtyards like in an Arabian garden, giving a fresh feel and fragrance.

For instance, we would like to propose bringing the arbor space for informal meetings from the current headquarters. Although the predominant material will be limestone, we consider it important to achieve a warmer feel by introducing some colored ceramic tiles forming “frozen” carpets at the reception area, as well as some color patches at the bar, cafe library, etc.

Regarding the future extension, our design offers the possibility to make this possible at a very low cost. An extra terrace would be excavated further down the hill to relocate the parking lot. Depending on the budget it could be roofed by a light structure or pergola, or either another by a slab generating another volume clad in stone. The current space for parking would be perfect to house a big open-plan office space, being lit by the front facade and the rear courtyard, which links diagonally all the spaces within the plinth.

All the above-mentioned qualities will contribute to making the visit a rich, surprising experience from the very moment the glittering volume is perceived from the distance. As one approaches the complex, a wide deep opening shaded with a stone screen invites visually to the access towards a big square. This square will be the center of social life and events like open air concerts, and will be in close contact with the art gallery and multipurpose hall by ramps running within courtyards. These ramps make all the public use spaces highly accessible, whilst accessibility will be granted in the tower by two elevators running along rigid structural cores.

In terms of sustainability, we are proposing some simple yet very effective mechanisms, most of them already used by vernacular architecture long before air conditioning entered the scene. Like ancient Palestinians used the materials they could find where they lived, we propose to use locally sourced limestone and ceramic tiles, not only saving on budget, but also improving the overall carbon footprint and providing durable and low maintenance materials. In order to save energy we employ every possible way of introducing natural light into the building, like courtyards, big openings and a light well or atria in the tower. Similarly we have arranged a section which allows cross-ventilation through the courtyards and the central atria in the tower, as well as proposed to install PV panels on the technical floor at the tower´s roof. As for the solar protection we have mentioned before the stone screening which will shade the tower´s glass surfaces, in addition to the deep cantilevers shading the wide openings we have proposed for the plinth.

As a conclusion we would like to emphasize that we are committed with a rational functional and economical design, reconciled at the same time with local ancient qualities that vernacular architecture provides, in order to achieve a simple and yet rich environment Palestinian people will feel as their own.

You must be logged in to post a comment.